Manager != Leader

“Do you consider yourself a manager or a leader?” This was the first question I asked Vince, the VP of Engineering at Sanctuary AI during my last month interning at the company. I had respected Vince’s active and hands-on management style since he’d first introduced himself one early morning in the lab, and as the Electrical Lead on UBC Solar, I was curious to hear how his answer would relate to my experiences as an engineering executive.

“A lead and a manager are not the same”, he answered. “You can decide to be a manager, but you can’t decide to be a leader.” He described that being a leader is a quality that others recognize in you, and that if you’re a good manager, people may grow to treat you as a leader.

At the time, I didn’t wholeheartedly agree with his statement, although I couldn’t articulate why. I began to question the qualities that would define a leader and differentiate them from a manager in an engineering context.

Leaders >? Managers

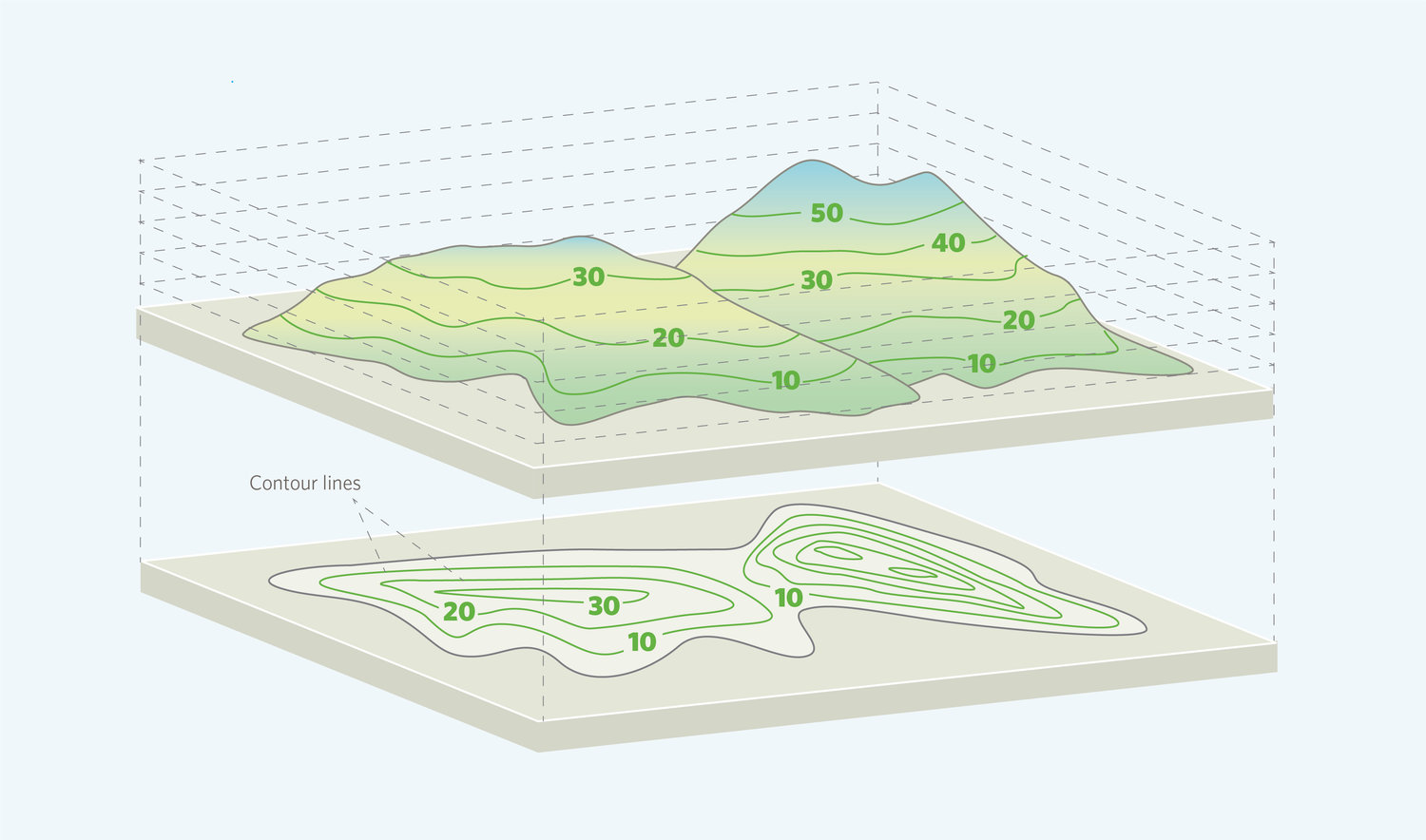

Being an effective manager is a step on the way to becoming an effective leader, however, one doesn’t necessarily guarantee the other. A leader must think about their team or organization at a higher level than a manager - similar to moving from a 2D plane to a 3D space. A leader has the ability to graph 2D contours while maintaining a visualization of the resulting 3D shape, while a manager may not be able to combine contours together to form an understanding of 3D geometry. Thus, a good leader must also be a good manager, while a good manager doesn’t imply a good leader.

More concretely, a manager’s goal is to solve a problem. By contrast, a leader’s goal is to empower the the members within their organization to work toward a shared vision, one which incorporates a need to solve associated problems. In this sense, a leader is proactive - they start with a vision and identify the problems that need to be solved to unlock the achievement of that vision. Then, a leader will work to get their team to buy into that vision. Finally, as this article from the Harvard Business Review states, the “result of this influence changes the way people think about what is desirable, possible, and necessary”.

Team members effectively influenced by a leader will begin to own the vision, and through it, any associated problems. The leader’s ultimate goal is to “create energy” by spreading the vision from their individual mind into an idea that’s shared and imbued into the team’s consciousness as a whole. A manager, on the other hand, will simply redistribute the energy already present within their team. They don’t focus on creating a shared sense of responsibility for an overarching team vision, instead assigning ownership of individual problems to individual team members.

An Analogy

A good basketball coach is both a manager and a leader.

As a leader, the coach will begin with their vision: to build the best basketball team in the world. They might translate this vision into the management-related goals of winning a certain competition, or beating a long-standing rival team - however, the coach won’t limit their focus to these immediate-future goals. As a leader, the coach will focus on empowering their team, getting them to buy into that vision of building the best team around. The coach will aim to evoke this sentiment in their team by re-positioning the member’s expectation of success - not “winning a game”, but rather “building a winning team” - and will aim to lead members to internalize and share that vision, such that the momentum generated by the team’s (now shared) vision will eventually outpace that of the coach as an individual.

To achieve this vision, the coach must be an effective manager. They will run drills, teach technique, and encourage exercise - doing so while highlighting both the team’s short-term goals and overarching vision. On game day, a coach will purely act as a manager - they’ll focuses on the problem of beating the other team, and will distribute the skills of their team to do so. During the match, the coach isn’t focused on the long-term learning and growth of the team’s skills, and instead is reacting to minute-to-minute challenges - making decisions that will achieve a win. However, after the match, the coach will transition into leadership mode, reflecting with the team on their performance and lessons learned that can be translated into future managerial goals and problems.

Personal Examples

During the past three years, I’ve been fortunate to work with two excellent managers. I consider both managers significant mentors in areas of my professional development, but only one do I consider a leader. Both mentors equipped me with the skills I needed to become an effective manager, and both exhibited traits that I would later come to realize made me an effective leader.

Jonathan at Ciena

During my January 2022 electronics hardware co-op at Ciena, I worked under Jonathan, a member of the Lifecycle Management Team (LCM) who’d taken it upon himself to be the manager of the team’s one co-op student in addition to his regular responsibilities.

At the time, the goal of the LCM team was to alleviate the chip shortages that were plaguing every electronics-related industry in the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This mandate resulted in well-determined problems being assigned to team members in the form of Jira tickets. Each team member had an assigned set of tickets from customers in the field, with a manager handling priority and looping other hardware teams in when necessary.

Ciena’s optoelectronics lab in Ottawa

Ciena’s optoelectronics lab in Ottawa

Managers >? Leaders

Jonathan was the best manager I’ve worked with, but was not leader. That said, in retrospect, he serves as a prime example that a leader is not always more effective than a manager. For example, the first task Jonathan assigned me was related to fault injection testing. Several modems were coming back from the field with strange behavior; when certain power rails went down, the entire card would freeze - an incorrect fault behavior that required a hard reset of the system. My job was to induce faults on the card’s numerous power rails, and to compare the actual behavior against the expected.

During a meeting with the original designers of that modem, we were referred to documentation of the fault injection tests that had been done on prototype cards, complete with the intended fault behavior of the card in various situations. Reviewing the document, we discovered that about a third of the power rails hadn’t been fault tested, nor had any intended fault behavior associated with them. I don’t doubt that someone at Ciena was leading initiatives to increase fault tolerance and reporting, however, their lack of follow-through - or in general, management skills - caused this gap in testing. This highlights the fact that an excellent manager can make up for an ineffective leader.

Jonathan the Manager

Jonathan’s philosophy as a manager was powerful in its simplicity - “I set them up, and you knock them down”. Jonathan was excellent at reacting to problems (chip shortages) and breaking them down into appropriately-scoped tasks for a second-year engineering student while providing ample opportunities for feedback and learning that grew not only my technical skills, but also my communication abilities and confidence as an engineer.

However, he never evoked a greater team vision - he didn’t need to. There was no step function from manager to leader that Jonathan needed to achieve in order to unlock a higher level of impact on the team. He maximized his impact by optimizing the resources of his team (specifically, me).

The LCM team out to lunch in Ottawa

The LCM team out to lunch in Ottawa

Morie at MPNH

I began volunteering at Mount Pleasant Neighborhood House (MPNH) in grade 11 (2019), and worked within a variety of different programs at the House until the end of my summer after first year university (2021). For the majority of my various roles, I worked with Morie, the lead of MPNH’s Family Literacy Outreach program. The program’s purpose is stated on MPNH’s website:

Family Literacy Outreach (FLO) matches trained, compassionate volunteers to work one-to-one with a newcomer family, so they can improve English literacy. Learning to read and comprehend English is essential for the caregiver to secure a job, navigate social services, and build relationships with others in this city.

Morie was an excellent manager, doing a lot of the same things that Jonathan did to help me succeed at Ciena - making me feel comfortable within the organization, building up my organizational habits and communication skills, and teaching me 1-1 in dedicated learning sessions. However, unlike Jonathan’s problem-oriented approach to the LCM team’s successes, Morie’s approach was vision-driven.

Just like the basketball coach, Morie’s vision wasn’t to “tutor a newcomer to Canada”, but rather to “build a program that’s effective at, among other things, tutoring a newcomer to Canada”. Morie emphasized empowering her team of volunteers, focusing on getting each one to buy in to the program’s vision of giving newcomer families the skills and confidence they would need to navigate their lives in Canada.

It’s important to consider the context within which Morie was operating. As a community organization primarily supported by volunteers, the boundaries of the organization’s mandate are virtually unlimited - unlike a normal company which has granular, well-defined goals and timelines.

- Note the broad vision of the FLO program - to support new immigrants and refugees in building relationships with their city. The goals and problems this vision encompasses are many - learning English, accessing social support services, finding employment, and helping the family’s children excel in school.

MPNH’s efficacy can be increased by whatever energy Morie decided to input. In this sense, as successful leads do, Morie was able to create energy within her organization and (as a manager) redistribute this ever increasing energy to support the program’s objectives.

Sharing Morie’s Vision

Both managers and leaders encourage their team to take more initiative and responsibilities within their organization, however, a lead will focus on getting members to take responsibility for the shared vision, versus a manager encouraging responsibility for a problem. In effect a good leader creates more leaders, while a manager might create more specialist problem-solvers.

During my time working with Morie, she was constantly generating new ways of helping her volunteers (like me) help the newcomers in her program. To illustrate this, I’ve jotted down a rough timeline of my roles at MPNH, each associated with a program Morie was directly leading or supporting.

- 1-1 tutor for a grade 2 student with a mild learning disability (volunteer)

- Group “Homework Club” tutor for high school-aged youth (volunteer)

- 1-1 online tutor for several students online during the first waves of COVID-19 (volunteer)

- Interim lead of MPNH’s Digital Literacy Program for seniors (paid summer student)

- Programmer within MPNH’s Family Literacy Outreach program, heading English Conversation Circles for immigrant women, and 1-1 tutoring for the mum’s children (paid summer student)

A key way that Morie encouraged me to take responsibility for MPNH’s programs was with her trusting, hands-off management approach. In my role as summer programmer for the women’s conversation club, Morie initially walked me through a session with the group, and then passed the responsibility for future lesson plans - including session topics and skill progressions - off to me.

This was a daunting problem - keeping a group of adult English-language-learners engaged and contributing equally to a shared discussion for over an hour was a level harder than any of the tutoring I’d done in the past. However, Morie increased the confidence I had in my own abilities by focusing on the fact that her and I were partners in the program’s vision of helping immigrants learn English to allow them to better integrate into their new home. It felt like she was saying “you’re going to lead this and I’m going to help out” - as opposed to a traditional manager, who might say “I’m going to lead this and you’re going to help out”.

Morie put me in positions that grew my role within MPNH from being responsible for certain problems and tasks to sharing responsibility and ownership over the House’s vision, and thus, the associated problems that I went on to manage.

Another Shared-Vision Success Story

One of the most apparent ways that Morie lead members of her organization to share responsibility for a high-level vision was when one of the mothers in the FLO program transitioned to being a volunteer at MPNH. The mother had been in the program for a few years, and, as her family gained more stability through upgraded English skills and increased support for her children in elementary school, she began to volunteer at the neighborhood house, helping distribute food to needy members of the community, and taking on administrative tasks within the House.

As a result of her leadership and successes in advancing literacy in BC, Morie was awarded the Council for the Federation Literacy Award in 2019. In that same year, MPNH also received the AMSSA’s Raisat Ali Khan Diversity Award. When receiving this award, Jocelyn Hamel, executive director of MPNH, stated:

“Diversity and social inclusion are basic tenets of our work at Mount Pleasant Neighborhood House. This is the red thread—our collective passion—that is woven throughout all our programs and service.”

Morie (left) with Honorable Melanie Mark, Minister of Advanced Education, Skills & Training, receiving the Council for the Federation Literacy Award at Mount Pleasant Neighborhood House

Morie (left) with Honorable Melanie Mark, Minister of Advanced Education, Skills & Training, receiving the Council for the Federation Literacy Award at Mount Pleasant Neighborhood House

Wrapping Up

When I asked Vince whether he considered himself a manager or a leader, I myself hadn’t considered the reasons behind my distinction between the two roles. Now, I believe that it’s possible to be both a leader and manager - one being a necessary condition for the other. As a lead, it’s your job to get your team members to buy-in to a collective vision - changing the way people think about what is desirable, possible, and necessary - while maintaining the effective management skills required to formulate that vision in terms of quantitative problem statements.