Clarity in Tacoma

Early this February, I found myself dancing my heart (and back) out at the 2025 Excision Thunderdome, the largest bass festival in Western North America. As my friends and I drove down to Tacoma, the festival’s host city, the people in the car who’d never been to an event at the eponymous Dome asked me what to expect from the city.

Seizing an easy opportunity for laughs, I reeled off stories of my first experience with the city last November - stepping over the pristine body of a racoon during our walk back along a narrow muddy path from the venue, a path that was bordered on one side by a multi-lane highway and on the other by a homeless encampment burning fires inside blue tarp tents. I introduced them to the “Tacoma Special” - vehicles with rusty gouges and loose bumpers, back windows smashed in one-too-many-times long since taped over with plastic sheets that were parked outside rows of boarded up buildings and pitted sidewalks. Hours after the laughter subsided and we drove further into Washington, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I’d missed some key elements in my description of Tacoma.

The next morning, I nursed a sore neck while plowing through a stack of pancakes at Alfred’s Diner and surveyed the surrounding booths filled with tradesmen from the water board and metalworks. How would they describe their city to out-of-towners? I thought about the old brick buildings housing family auto shops, the lumber and steel-transporting railway that cut through the city’s center. I remembered lasers glinting through the windows of an after-party held in an old train station that had been converted into an art gallery. I thought back to last November when, exploring a trail outside of a neatly-kept church, I found a hand-painted box housing a take-a-book leave-a-book public library, and that the same night we’d watched as crew of street racers drifted circles around each other in souped-up Mustangs.

As I thought about the steps one would need to take to revitalize Tacoma, I recalled a book I’d seen floating around several urban planning reading lists - the Sprawl Repair Manual - and decided this was the perfect opportunity to dig into its pages and discover whether they held a solution to my questions.

The Sprawl Repair Manual

The Plague of the Suburbs

In January 2022, I moved to Kanata, a suburb of Ottawa, for a four-month internship. Never having lived in the suburbs before, I was immediately shocked by the scale of open and unused land, by the massive office campuses I walked past each morning, and most of all, by the lack of people. Each Thursday I would make the half hour trek through knee-high snow to the local Sobeys (located in a strip mall next to a six lane highway), and never saw more than one or two folks walking on the sidewalk. In the spring when the snow melted, I hauled my landlord’s old bike out of the garage and discovered that a five-minute ride past the highway would take me into acreages of rural farmland.

On the flight back to Vancouver, I felt tears prick at the corners of my eyes when I first caught a glimpse of the gulf islands far below. The entire time I’d been in Kanata I’d missed the city of Vancouver just as fiercely as I’d missed my best friends.

While the suburbs aren’t the happiest place for a homesick city boy, they’re also not happy or healthy for their full-time residents.

In his book Happy City, Charles Montgomery, an influential urban planner based in Vancouver, analyzes the defining characteristic of the suburb - the car - through the choice people make of how far they travel to work. People who endure long drives experience higher blood pressure and more headaches than short commuters. They’re frustrated more easily and tend to be grumpier when they get to their destination. But isn’t this situation a simple cost-benefit analysis? People would only put up with longer commutes if they enjoyed greater benefits from cheaper housing or bigger, finer homes or higher-paying jobs.

Digging deeper, Montgomery examined the work of Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer from the University of Zurich, who compared German commuters’ estimation of time it took them to get to work with their answers to the question, “How satisfied are you with your life?” In general, Frey and Stutzer found that the longer the drive, the less happy people were. Keep in mind, they weren’t testing for drive satisfaction, but for life satisfaction. Their discovery wasn’t that commuting hurt, it was that people were choosing commutes that made their entire lives worse. This fact blows a hole in the long-accepted argument that the free choice of millions of commuters can sort out the optimal shape of the city. In fact, exchanging a long commute for a short walk to work has the same effect on happiness as finding a new love.

Studying Sprawl Repair

The Sprawl Repair Manual defines the downsides associated with suburban sprawl in more binary terms, but terms that are highly relevant to the time the book was written; 2010 to be specific, right after the US economic crisis in 2008. This was a time in history when governments, developers, and citizens realized that the kind of suburban development with little regard for economic or energy usage considerations that we know today might be economically unsustainable for future generations.

1st Generation Suburbs: Traditional growth patterns formed streetcar and railroad communities outside city limits.

1st Generation Suburbs: Traditional growth patterns formed streetcar and railroad communities outside city limits.

2nd Generation Suburbs: Conventional suburban development created car-dependent sprawl along new highways.

2nd Generation Suburbs: Conventional suburban development created car-dependent sprawl along new highways.

3rd Generation Suburbs: The Exurbs.

3rd Generation Suburbs: The Exurbs.

This type of unchecked sprawl began after World War II, as baby boomers with new wealth and automobiles migrated to new developments further and further outside of the city, and despite the 2008 crisis, the development industry continues to produce sprawl with the support of government policies, the financial industry, and regional planning practices. The suburbs are easier to plan and finance, and faster and less complicated to build due to limited regulations. However, with price of gas rising, long commutes to or from exurban locations become economic disadvantages, something which turns the whole game of suburban development on its head.

In contrast to sprawl, complete communities are economically robust because they include a variety of businesses that support daily needs, and nearby residents work at and patronize those businesses. They’re socially healthy because many generations with diverse incomes and backgrounds live and interact within them. Complete communities are livable because of their comfortable human scale. They are environmentally superior because they are compact, saving land and natural resources. Since sprawl isn’t compact, it consumes excessive amounts of farmland and valuable natural areas. Haphazard sprawl development has disconnected natural areas, with the result that neither the human nor the natural habitat has retained its integrity.

Sprawl repair at its core seeks to create complete communities from disconnected sprawl by identifying and enhancing centers and edges.

Key Principals

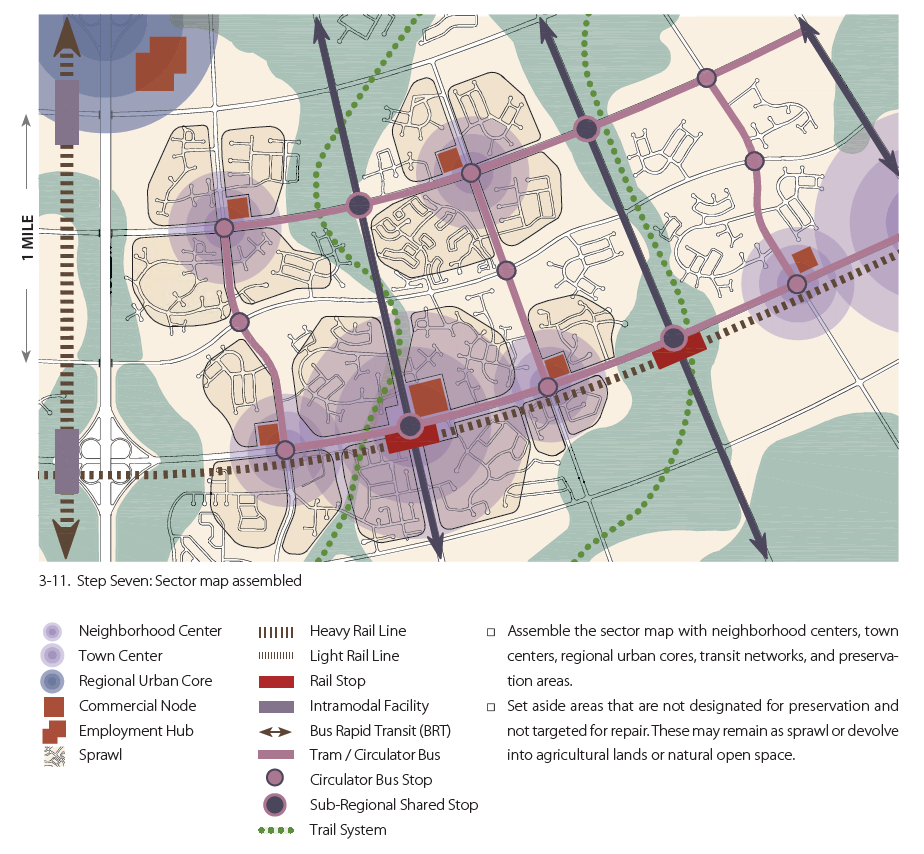

The Manual’s recommendations are presented at varying scales - regional, neighborhood, block, and even building, but have similar themes and recommendations throughout. In particular, establishing neighborhood structure and connecting it to the larger region is the greatest design challenge encountered in sprawl repair - a challenge to which they outline a seven-step solution:

- Determine Sprawl Repair Domains. Repair should begin at the regional scale, by identifying the areas that hold the strongest potential for employment and for supporting viable urban centers that will sustain economic growth and minimize the need for long commuter trips.

- Delineate Preservation and Reservation Areas. Use a Rural Boundary Method similar to that proposed by Benton MacKaye, the initiator of the Appalachian Trail, to identify and reclaim environmentally sensitive open-space networks damaged and obscured by sprawl.

- Prioritize Commercial and Employment Nodes. Unfortunately, the manual doesn’t expand much further on this important point.

- Prioritize Potential Transit and Infrastructure Networks. Focus on corridors connecting existing urban cores (traditional cities and towns) with potential regional urban cores, town centers, and neighborhood centers. The focus on infrastructure should also be expanded to water, communications, and energy delivery.

- Identify Sprawl Repair Targets. These specific locations for intervention and repair are areas where transit and job potential overlap, with possibility of achieving residential density to support transit.

- Implement Transfer of Development Rights. Leverage governmental mechanisms that assign legal development potential allowed under zoning ordinances from an area to be protected to a property in an area slated for growth or redevelopment. For example, a local government can transfer the right to develop land in a reservation area to an area identified for high development priority.

- Assemble Sector Map. The principal of the pedestrian shed - a circle with a quarter-mile radius (0.4km), that being the distance that can normally be covered in a five-minute walk - can be used to define neighborhoods and the transit networks that will connect them.

After sprawl repair targets and infrastructure modifications have been identified on a regional scale, architects and planners can begin tackling the local issues associated with the single-family subdivisions that dominate the suburbs.

In particular, dwellings in these zoning regions are usually monolithic in design and represent one type of use - single-family housing. There are no “destinations” within a neighborhood, and certainly none within walking distance. Long blocks with numerous cul-de-sacs and dead-ends limit walkability and isolate sections of a neighborhood from each other. Finally, ample greenspace that could be used for small-plot farming or public parks is wasted on private, water-intensive setbacks and lawns.

To begin creating vibrant neighborhood units within the areas targeted for repair, the pedestrian shed should act as a discernable center with a transit stop, plaza, and green or memorable intersection. Within the pedestrian shed, new buildings can be added and existing ones repurposed or retrofitted - for example, increasing the number of affordable units in an area by converting existing single-family houses into duplexes and multifamily buildings and adding accessory units and apartments above shops. At the same time as new schools and community centers are being built, break down long suburban blocks into wider, shorter blocks, with a specific focus on punching paths through those walkability-killing cul-de-sacs.

Existing infrastructure should be upgraded and expanded to handle to handle higher population densities, including on and off-site treatment of stormwater, and technologies like pervious paving, channeling, storage, and filtration can be used leveraged as suggested by The Light Imprint Handbook.

While the Manual provides few concrete examples of sprawl repair in action, I discovered an example master-planned community born out of the sprawl of an old mall that completed its first phase a couple years after the Manual was released.

Belmar in Lakewood

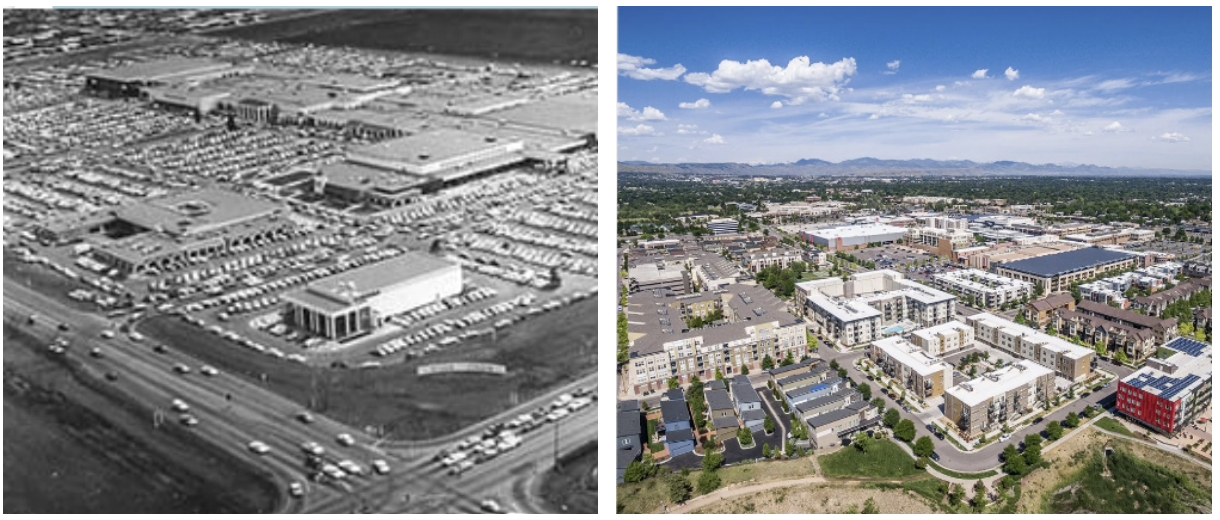

Opening to great fanfare in 1966, the Villa Italia Mall was the closest thing that Lakewood, a suburb of Denver, had to a town center. Yet, by the mid 1990s, the last of Villas tenants had moved out of the dying mall, leaving the area relegated to a blight-infested future - that is, until the Southwest Quadrant committee, a citizen’s advisory group, banded together and began considering the area’s future and laying out guiding principals for redevelopment. After a lengthy consulting process, their vision was Belmar, a 22-block downtown for Lakewood that would combine a mix of condos, plazas and office space with a strong retail business presence.

In 2005 after finishing the cleanup of toxic PCEs that the mall’s two dry cleaning businesses had leached into the underlying soil, the massive buildout of the site began in earnest. As of 2014, Belmar had:

- 1.1 million square feet of retail space

- 900,000 square feet of office space, which includes a 250-room hotel

- 1,300 residential units

- 9 acres of parks, plazas, and other public spaces

Today, Belmar continues to expand, and is frequently cited by enthusiastic New Urbanists as one of the best dead-mall retrofits in the USA. If you were to look at before and after images of Villa and Belmar, you’d see a redevelopment straight out of the pages of the Sprawl Repair Manual.

This is precisely why urbanist Kevin Klinkenberg argues that Belmar represents everything that Sprawl Repair gets wrong.

The Misguided Efforts of Sprawl Repair

Kevin served as the Executive Director of the Savannah GA Development and Renewal Authority for four years, and previously ran the consulting firm K2 Urban Design. In 2015, Kevin began to debate the concept of Sprawl Retrofit with urban planner Robert Steuteville, arguing that Sprawl Retrofit is a pleasant concept but not a viable solution to widespread sprawl.

Kevin used Belmar as an example of the deficiencies of sprawl renewal, noting that while the shops at Belmar may be a walkable distance from its residences, the development as a whole remains an island in a sea of sprawl. Google Maps lists transit from central Denver to Belmar as an hour-long, two-transfer bus ride, and a street view of the area surrounding Belmar shows it as a stroad-ridden suburb.

Belmar’s complete overhaul of the mall area also contributed to increasing the areas’ energy usage. While a 1.7MW solar array was installed in 2008 (and, at the time, was the largest rooftop solar array in the western United States), this source of renewable energy only supplied Belmar with 5% of its annual energy use.

Indeed, this distinction between Belmar’s redeveloped sprawl and true urbanism was inadvertently highlighted by Belmar’s Chief Development Officer when he stated;

“Belmar brought together a lot of uses that might otherwise have dispersed around the landscape. It will make Lakewood more viable in the long run economically, as a first tier suburb.”

What cities and people desperately need are coherent, contiguous neighborhoods in every region where cars aren’t necessary - not multiple, tiny pockets of so-called “walkable” developments. These locations are too difficult and expensive to make marginal improvements to drivable suburbia, and actually build mistrust, as people’s lives haven’t been transformed by the promised “walkable urbanism”. Indeed, when honestly considering how to best improve the lives of the less fortunate in society, we would want them in places of maximum opportunity for access to jobs at a low cost - not scattered about in suburbia. It’s more likely these places will collapse of their own accord, rather than being transformed into walkable urbanism.

In fact, Kevin noted that in the timespan it would take to make similar areas into C+ versions of walkable urbanism, talented design teams could redevelop a dozen older neighborhoods or build several new towns on greenfield sites.

Speaking at the Congress for New Urbanism (CNU) in 2018, Kevin’s presented his high-level arguments against sprawl repair.

Our primary struggle as urbanists or new urbanists, is with bigness and our system of mass production. Jane Jacobs described it in cities as cataclysmic money. Too-big projects. Fragile, too-big that do in fact fail. And fail disastrously. Everything that we love about urbanism, virtually everywhere in the world, is about what was built in gradual increments.

Suburbia, or sprawl as we tend to interchangeably call it, is all about bigness and mass production. It’s planned in huge increments of land, underwritten by Wall Street, has roads delivered by state DOT’s and built often by regional or national developers & builders. It’s an incredible, wildly successful, efficient system for delivering development on a mass scale. And it’s absolutely, fundamentally at odds with successful, walkable urbanism.

He summed up his arguments by saying “let urbanism be urbanism, let sprawl be sprawl.”

The Manual’s Limitations

Kevin’s points against sprawl repair aligned with certain themes I’d noticed as I made my way through the Sprawl Repair Manual. I wanted to believe in the book’s message, but my faith in its recommendations that weren’t backed up by real case studies kept slipping under an increasingly critical eye.

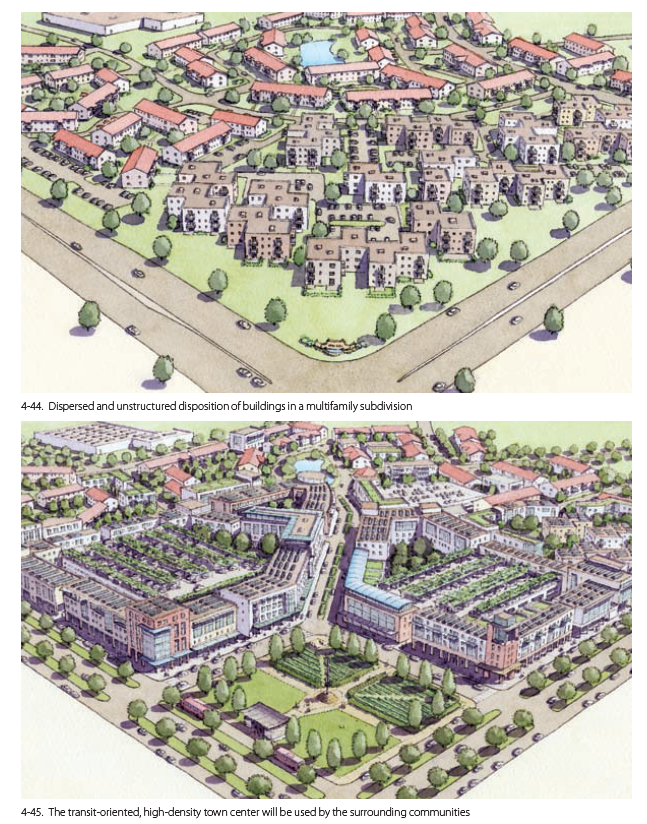

Take the example of repairing a sprawling multi-family subdivision, presented in the before-and-after sketches below:

As Kevin noted, this type of redevelopment would still be highly car-dependent, as evidenced by the vast areas of parking space allocated in the center of each residential complex. The blocks in this image are still long, narrow, and not shaded by greenery, just as the public park contains no benches, playgrounds, or other amenities that would make local residents compelled to use it - residents who themselves are conspicuously missing from most of these images of master-planned developments.

A core suburban issue is the lack of place-specific architecture - designs that take into account a local area’s natural ecology and climate when considering everything from a building’s materials to its shape. Unfortunately, the Manual continues this trend by leaning heavily on the crutch of standardized, energy-intensive designs in its illustrations. As Kevin would say, the buildings, parking lots, sidewalks, and parks presented page-after-page in the Manual look like the same version of a C+ city.

A chuckle-inducing example of this complete lack of place-specific architecture can be seen in the image below.

Obviously, the authors of this book never worked with wind turbines before. If they had, they’d likely understand that putting five wind turbines in the middle of a parking lot behind a commercial building is not the most feasible of activities. (Additionally, who’s maintaining that rooftop garden - a small, master-planned community that doesn’t feel ownership over its new semi-urban environment certainly won’t.)

On the topic of energy usage, the Manual never specifies how much energy would be required to undertake the types of transformations it recommends. How many miles of suburban sewer infrastructure would have to be ripped up and augmented for these relatively small communities? How much embodied carbon would be created by demolishing acres of concrete parking lots and building new rows of new three or four-story apartments?

And then there’s the money. No comparison is presented between the cost of upgrading miles of insufficient rural infrastructure and the option of relocating residents to a location with appropriately-sized infrastructure. There are no long-term projections for tax revenues generated within an upgraded suburb versus what could be generated if that same investment was directed to a struggling downtown core. How about the transit that’s connecting these pedestrian sheds? Should hundreds of millions be channeled into creating and maintaining several bus routes between communities of 100 - 300 people, or should that money instead be directed to the creation of a high-speed rail system between two existing densely-populated cities, as is proposed for San Francisco and LA.

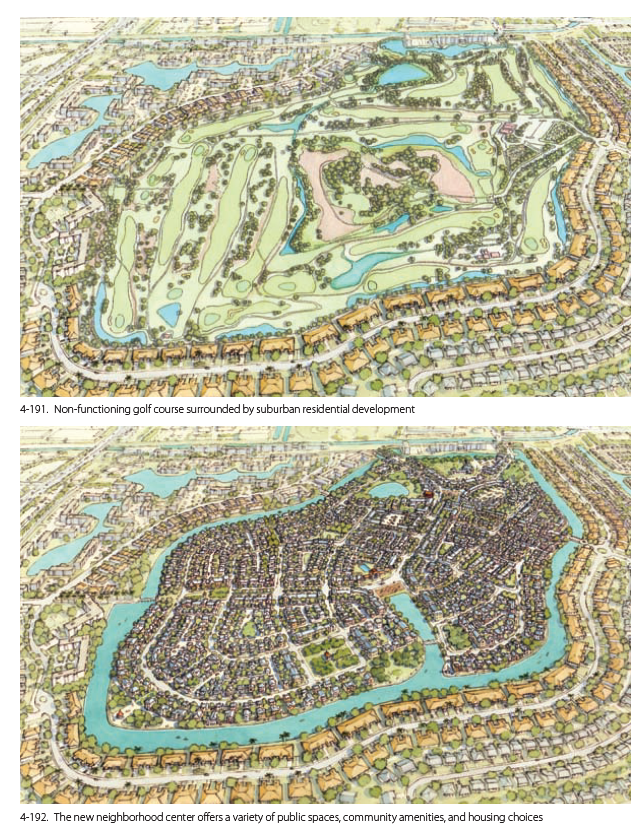

An image from one of the final chapters of the Manual lays bare the authors’ grand visions on the topic of sprawl repair.

The exorbitant amount of money, materials, and carbon that would be required to create this type of terraformed development mean it would simply never occur. Over the course of the book, the Manual’s tenant of identifying and enhancing centers and edges fell prey to the ideals behind doomed projects like The Line.

Of course, that isn’t to say that the suburban golf course redevelopment laid out in the first image should be maintained. Instead, the principals of Regenerative Design, as championed by Bill Reed, the co-founder of the US Green Building Council and the LEED standard, do a better job of encouraging the land to “remember” its past ecology and working with this restorative potential. An excellent example of this is showcased in Reed’s work on the Brattleboro Food Co-Op.

When is “Sprawl Repair” Appropriate?

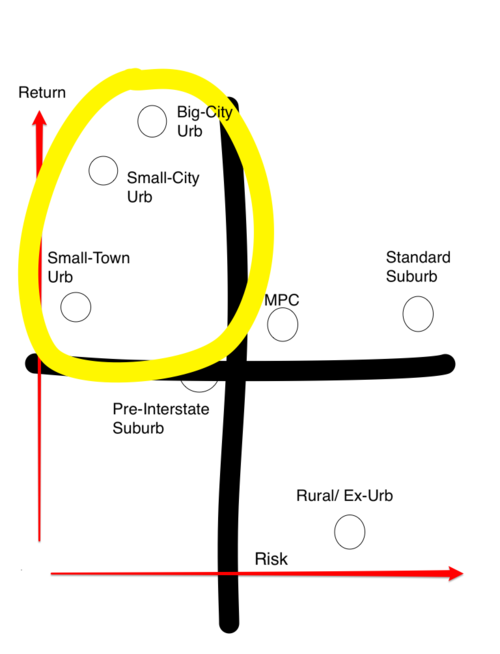

Instead of focusing on expensive, expansive sprawl repair, Kevin argues that planning discussions should be focused on delivering excellence. If the best that sprawl repair can afford is C+ cities, then it isn’t worth the the time, energy, and money that could be better spent elsewhere delivering truly change-making, meaningful communities. Specifically, planners should focus on more realistic cost/benefit scenarios in small towns and cities. It’s important to remember that most places in North America aren’t like DC, New York, or San Francisco - they need restorative attention given to their foundational old, urban neighborhoods that were built well originally.

In order to distinguish between communities deserving of repair and those that should be left to decay into nature, Kevin defines 4 types of sprawl.

- Pre-interstate suburbia

- Standard subdivision suburbia

- Master-planned communities

- Rural/Exurban sprawl

Pre-interstate suburbia (#1) is the lowest risk and has the potential for the highest return on investment (both socially and monetarily), and so is the only type of sprawl with the potential to be restored to excellence.

This type of community was originally built with reasonably-connected street networks since it wasn’t based on the mile-square grid that arrived with the interstate system. These are places that might have established public spaces surrounded by smaller homes that can reach the affordable needs of those wanting to take on a smaller mortgage.

For this pre-interstate suburbia, regional organizations should create detailed masterplans and codes that immediately shift development focus to making old downtowns successful as independent, walkable neighborhoods by revitalizing the bones of the many pre-1940s structures, reforming greenfield development processes, and building a network of bike paths.

Only after this should regions consider working with owners of office parks or regional malls to develop these sites into town centers, Even then, this will be a tough sell that will produce isolated islands of walkability requiring large amounts of parking. These places are generally in the hands of single owners, and thus lend themselves to big-scale projects and interventions, instead of providing the opportunity to create the kind of gradual change that makes for great human settlements.

I found Kevin’s insistence on only delivering excellence by intentionally retrofitting existing pre-interstate downtowns to be profoundly aligned with my philosophy that through reducing the energy usage in our built environment (here, by working with the existing potential of small downtowns), we can more meaningfully connect people to community. This focus on excellence and revitalization of community was embodied by the journey of one music venue in a small town in North Carolina at the end of the 20th century.

The Orange Peel

In 2008, Rolling Stones magazine named The Orange Peel as one of the top 5 rock and roll clubs in the USA. Since then, artists from Bob Dylan to Ziggy Marley and from Ween to Wilco have performed to sold-out houses in downtown Asheville. Yet, The Orange Peel’s building was by no means always home to one of America’s top rock venues.

Apart from a brief stint as an auto parts warehouse, The Orange Peel had been abandoned by the end of the 1970s. Like many of the buildings in Asheville’s downtown, the building’s elegant old structure was boarded up and encased in aluminum siding as highways and liberal development policies sucked people and commercial life into dispersal - the suburbs. However, one man refused to allow his downtown to decay into oblivion.

In 1991, Julian Price, heir to a family insurance and broadcasting fortune, poured everything he had into nursing Asheville’s old downtown back to life. Under his newly-founded company Public Interest Projects, Price bought and renovated old buildings, leased street-front space out to small businesses, and rented or sold lofts above to new wave of residential pioneers. First, a vegetarian restaurant opened, then a bookstore, a furniture maker, and in 2002, The Orange Peel opened its doors to musicians and metalheads alike.

After Price’s death in 2001, Joseph Minicozzi, a young architect from New York City, and Pat Whelan, an attorney, had to battle city officials who saw such little value in downtown land that they wanted to place a prison in the middle of terrain perfect for mixed-use redevelopment.

To fight back, Minicozzi posed a question: what’s the production yield for every acre of land in and around Asheville? In downtown, a converted 1923 JC Penny building housing shops, offices, condos took up 1/4 acre, and paid $333,000/acre in property tax. A Walmart at the edge of town, with it’s large paved parking squares, consumed 34 acres, and paid $50,800/acre in property tax. This simple calculation laid the economics bare to the city council - Asheville received more than 7 times the return for every acre on downtown investments versus those at the city limits.

.jpg) The old JC Penny building in downtown Asheville

The old JC Penny building in downtown Asheville

In addition to providing property taxes to the city, the JC Penny building employed 14 people, which, when compared superficially to the Walmart’s 204 employees, might’ve seemed like a compelling reason to encourage outskirts development. However, a more revealing statistic shows that the Walmart really only provided 6 jobs/acre, compared to the 74 jobs/acre nurtured by the JC Penny building.

The relationship between energy and distance means large footprint sprawl development patterns actually cost cities more to service than they give back to taxes, a common developmental trend of sprawling growth producing deficits unable to be overcome with new growth revenue. As a result of this push by Minicozzi and Whelan, the city changed zoning policies, allowing flexible use for downtown buildings, livelier streetscapes and public events, and stopped forcing developers to build parking garages, instead moving to the a user-pay parking garage model.

Asheville’s reborn downtown has become greatest supplier of tax revenue and affordable housing in the county due to the relief of commuting paired with high-end lofts and modest apartments. By paying attention to the relationship between land, distance, scale, and cash flow, a dedicated group of citizens worked to build more connected, complex places to support the city in regaining its soul and good health.

Circling Back to Tacoma

While working on this article at a café in Vancouver, my friends brought up the possibility of driving down to a concert in a venue just outside of Tacoma. The venue, an old naval hanger repurposed by the City of Seattle into a multi-use event space, reminded me of the success Asheville’s developers had with The Orange Peel and other downtown buildings, and I wondered how this developmental excellence could be applied to Tacoma’s pre-industrial downtown.

It turns out that Tacoma has put into motion several plans for its revitalization. After years of community feedback and revision, Tacoma finally declared its housing affordability initiative, Home in Tacoma, in effect as of the start of this February. This update to zoning regulations to allow greater flexibility and density in housing types is a first step towards Pierce County’s Vision 2040, an ambitious plan which includes growing Tacoma’s population by more than 30% - to 325,000 residents - over the next 15 years.

As part of Vision 2040, BloxHub, a Nordic urban planning firm, developed a master plan for Tacoma’s Downtown Theatre District. Despite key development projects during the 1990s, including the expansion of the University of Washington Tacoma, the introduction of the state’s first modern electric light rail system, expanded protected bicycle lanes, several street/alleyway activations, an established arts and museum district, and a restored urban waterfront, much of downtown and its surroundings still bear the imprint of car-centric planning. Major roadways like Interstate 705 create barriers between downtown and waterfront areas brimming with community potential, limiting access for pedestrians, public transit, and cyclists.

Tacoma’s ambitions of increasing public transit, walkability and bikeability combined with regional affordable housing initiatives are grand, and rightfully so. These are the types of revitalization project that, like Ashville’s downtown, have enjoyed tremendous success in the past, and can work to deliver excellence and positively impact communities the future.